- Overview

- EcoDevo - Biol 4370

- Evolution - Biol 3306

- Scientific Communication - Biol 6312

- Biology & Biochemistry Undergraduate Research Training (BURT) Program & Course (BIOL/BCHS 3396 & 4396; AKA Senior Research Project)

- Major Interest Group (IDNS 2197)

- (Award Winning!) GalapaGo! Research-Based Learning Abroad Program & Preparatory Course

- The Evolution and Development of Polyphenisms

- STEM Careers Seminar: And you may ask yourself, how did I get here?

- Houston Zoo Paid Summer Internship

(Award Winning!) GalapaGo! Research-Based Learning Abroad Program & Preparatory Course

Note: The Program is not being offered in 2024-25; contact the Program leaders below for information on the 2025-26 Program

The GalapaGo! Research-based Learning Abroad Program has three main components. First, students participate in a required spring-semester preparatory course that readies them for the cultural immersion and scientific research they will experience on the islands. Second, there is the abroad portion of the course, which starts in May and continues for roughly one month. During this portion of the experience, students live with local host families and conduct Galapagos-based research with scientists from around the world. Third, roughly one month after returning to Houston, everyone gathers for Galapafest!, where we make meaning of our experiences by sharing narrative-based projects about our personal and professional growth during the Program. Details about each of these components, scholarships to help support participation in the Program, etc., are provided below. The Program is open to any major. See the 2020 Trip Brochure here. If you have any questions, please contact Drs. Azevedo, Frankino, or Hanke (contact info below).

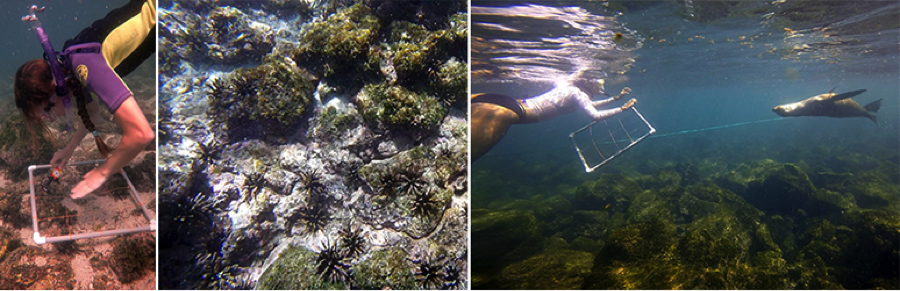

Practical Notes: The research, and getting around the islands, is physically strenuous. The islands are along the equator and so the sun is direct and hot. Much of the research requires extended snorkeling around San Cristobal. Students can expect to walk approximately 10 miles a day and spend 4-6 hours in the cold water daily. Thus, you need to be in reasonably good physical shape and comfortable swimming in the sea in depths of up to 20 feet to participate. Swimming competence will be demonstrated by passing a custom GalapaGo! swimming performance test before the end of the fall semester.

While fluency in Spanish is not necessary to take the trip, some proficiency with the language is very useful in your host home, in town, on on excursions and while doing fieldwork. Thus, we will provide an avenue to improve your Spanish fluency during the course, however, you should make learning as much of the language as soon as you decide to go on the trip. Sign up for notices about information sessions and such here ! When you are ready to apply to the Program, then complete this form - do not delay, as we can only take 30 students each year.

Overview - The Galapagos

The volcanic islands of the Galapagos archipelago are diverse, important and beautiful. They have a unique, complicated geologic history and experience strange weather patterns owing to interactions between currents of sea and air. Their isolation, geologic diversity and climate has produced large numbers of species that occupy the land, sea and sky of the islands - species that exist nowhere else in the world. This diversity kindled ideas that have become the foundations of how we understand geologic and biological evolution, and offered some of the most important data in modern biology. Thus, it is not surprising that in 1978 the United Nations declared the Galapagos a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Yet, in recent times, the islands have become less isolated. The double edged sword of ecotourism offers economic promise but risks harming the delicate geology and biology of the islands. Non-native species threaten endemics and the unique ecosystems they inhabit. Moreover, changing climate will alter the ocean and wind currents that control the archipelago’s weather and make possible it’s staggering marine diversity. To combat these problems, programs at forefront of conservation biology that integrate sociology, economics, biology and policy have been developed and implemented in the Galapagos.

GalapaGo! Preparatory Course (BIOL/HON 4302)

This course is about preparing for the GalapaGo! Research-based Learning Abroad trip to the Galapagos Islands each summer, and is open only to students participating in the full GalapaGo! Program. The class is offered in the spring, and culminates the trip to the Galapagos Islands, where students will spend approximately one month assisting faculty with ongoing research projects. In addition to preparation for this immersive research experience, we will use the Galapagos Islands as a model to explore several topics in geology, evolutionary biology, history and conservation. The course will include integrative projects, include readings, student-led discussions, films and lectures.

Course Mechanics: The 3h course meets twice weekly during the spring semester for 1.5 hours; the balance of course time will be invested conducing research on the islands. Grades will be earned according to the following breakdown: 33% from in-class participation and UH-based assignments, 33% from research performance and presentations on the islands, and 33% based on a final project to be completed after returning from the trip. As the course is in the spring and the trip over the summer, all students will receive a grade of I (incomplete) at the end of the course in May, with final grades being assigned after your projects are submitted for evaluation. Please note that a short-term ‘I’ for a course like this will not affect your transcript negatively. Students must enroll in the class to take the trip, and they must take the trip to enroll in the class. Students must take the course to participate in the trip, and only travelers can enroll in the course. Students will enroll by Dr. Hanke once a deposit has been made by students with approved applications. Enrollment is limited to 30 undergraduates. Course Details HON 4302/BIO 4302; Spring 2019 - TTh 1-2:30 regular session. Instructors: Dr. Ricardo Azevedo; Dr. Jake Danne; Dr. Tony Frankino; Dr. Marc Hanke; Dr. Martin Nunez; Dr. Becky Zufall

Trip to the Galapagos - Scientific Research & Daily Life

The trip is organized in conjunction with the Universidad San Francisco De Quito. In partnership with the University of North Carolina. USFQ runs the Galapagos Science Center, a research station in Playa Mann on San Cristobal Island. At the research station and through the adjacent GAIAS program, you will interact with faculty from USFQ and around the world working on projects in the islands. Descriptions of specific research projects, and how you will contribute to them, are provided below. Previous projects focused on (i) identifying and quantifying sea turtle foraging habitat and how it is used by the turtles; (ii) quantifying the impact of sea urchin foraging on diversity in shallow bays; (iii) seeking relationships between behavior of introduced dogs and viral diseases in sea lions; (iv) looking at the effects of humans on water quality on the islands; (v) quantifying the levels and origins of plastic pollution in the islands, and (vi) working to quantify and facilitate the conservation of endemic species.

Students will be housed with local families that have been thoroughly vetted and have participated as hosts in past years. Breakfast and dinner will be included daily. We will also have a central UH-Base Camp where we will gather as a group daily to share our experiences, talk about our research, and have fun. The trip will include:

- a few days on the mainland around Quito seeing historical sites and natural wonders just after arrival

- week-long rotations through 3-4 different ongoing research projects on the islands. Research will happen 4-5 days a week for roughly 1/2 the day and the balance of your day is free time. Sundays are ‘family days’ where you will travel the islands, experience local cultural events, etc., with your host families.

- weekends include planned Saturday excursions to distant locations on and around San Cristobal. These include snorkeling at Kicker Rock and trips to the highlands, San Cristobal Tortoise Conservatory, Puerto Chino beach, etc. These trips will allow you to get very close to some of the endemic species and experience pristine landscapes of the islands.

Program Cost and $cholarships

We estimate the cost to each student will be no more than $5,500; of this, some money can be awarded to most students from awards from UH Learning Abroad and from the Honors College for Honors students. Moreover, from 2022/23-2025 we can offer NSF Scholarships to pay up to all of the cost of participation in the program!

NSF-GalapGo!Scholarship Applications are open for the 2023/2024 Program

To qualify for the NSF-GalapGo!Scholarship, students must:

- Be at least three semesters away from graduation

- Have a GPA of at least 3.2 based on UH coursework

- Be eligible for federal Pell Grants

- Be an NSM major and not tracked for medical or other professional school

- Be eligible for at least some travel awards from awards from UH Learning Abroad, the Gilman Organization, etc.

- Be able to withstand the physical rigors of field work in the Galápagos and pass the swim test required of all participants

- complete and submit all forms by the deadline (noon on Friday, October 21)

Through a National Science Foundation Grant, we are able to offer several GalápaGo Scholarships which offset the cost of participation in the program. These scholarships will be applied to the cost of the trip (airfare, housing, daily breakfast and dinner, island excursions), a monthly stipend, and tuition for the spring preparatory course. Five full scholarships of ~$8,000 and four partial scholarships of ~$4,000 will be awarded. While any student can apply to the Program, applications for the GalápaGo Scholarships will be considered only from students eligible under these criteria.

The Research in Research-based Learning-abroad

Students rotate through a set of research projects, spending about one week on each. The number and identity of projects to which a student is assigned depends on the trip year, the number of UH students in the program, and individual student interest, ability and preparation during course. Typically, students are assigned to rotate through three sequential projects, however, the ambitious can arrange their schedule to participate in as many as three projects per day. This means that there are many research opportunities for students, some formal and some informal.

The projects are divided into two broad categories. The first set of projects revolve around the establishment, growth and use of a foundational resource - algae - that defines much of the marine animal community structure in the costal regions of the Galapagos. The second set of projects revolve around health on the islands. The components of these two broad research programs are described below briefly. Additional projects, not described here, may be offered in a given year.

I. Algae

Algae grows on the rocks in the intertidal and euphotic zone. It serves as a food source for sea turtles, sea urchins, and many species of fishes. In some places, these different consumers appear to compete for algae, and the presence and abundance of species is affected by the physical the structure of the habitat, the presence of other (potentially competing) species, and the quality and amount of algae. Four projects are aimed at understanding the interactions among these factors that shape the costal animal community.

Ia. Algae recruitment.

As noted above, in many ways, algae serves as a common food resource for many organisms and therefore helps to define the biological communities along the coastline. This project seeks to determine what physical and chemical characteristics facilitate or inhibit the recruitment and growth of algae. To do this, students affix plastic plates to intertidal rocks at several different sites and measure algal recruitment.

The plates have one of two colors (light/dark), which gives them different thermal properties. Moreover, the plates contain a small mesh section which is filled with substrate. This substrate varies in texture or chemical composition. Comparison of algal colonization and growth rates on the plates among different combinations of plate color, substrate texture, and substrate chemistry, reveals the characteristics that affect the abundance of the algal resource in a given area.

This project teaches a bit of algal biology, chemistry, tidal ecology and microscope techniques. It also takes students to several sites around the islands. Some hiking is involved, and some physical work mounting plates on slick intertidal rocks is required. Thus, you need sturdy shoes that you can get wet.

Ib. Sea turtles.

Sea turtles eat the algae that grows on well-submerged rocks. This project seeks to determine how the spatial use of sea turtles is affected by the distribution of algae. To do this, students swim with the turtles at several study sites, taking photos for use with (turtle) facial recognition software to identify individuals. At the time of the sighting, students note the sex, activity, and location of these same turtles. Finally, students sample habitat composition along transects at each site. Over the long term, associations between the spatial use of individual turtles and habitat composition can be established.

This project requires some hiking to different research sites and several hours of intense snorkeling in cold (ca. 20C) water each day. Many, if not most, students wear wetsuits; as a poor fitting wetsuit ether does not keep you warm or restricts your movement, you may wish to consider bringing your own if you anticipate difficulty finding a suit that fits you well. You must be a strong swimmer to participate. The project also includes at least one day in the lab working with the turtle facial recognition software. There may also be opportunities to work with the USFQ researchers doing mark-recapture based projects with the turtles, mounting cameras to free-range turtles, etc. In addition to learning about the autecology of different species of sea turtles, this project will teach some geometric morphometrics, the statistics behind and interpretation of mark-recapture studies, and some tidal ecology.

Ic. Sea urchins.

Different species of sea urchin occur in widely varying numbers in the Galapagos, and each has a potentially strong impact on the algae on which they forage. This project seeks to determine the distributions of these urchins and relate these to physical characteristics in the environment. To do this, students place quadrants along underwater transects, estimate the algal cover in the quadrants, and count, identify to species, and measure (with a caliper) all sea urchins in the quadrants.

This project includes the same study sites as the sea turtle project, and requires several hours snorkeling in the cold water. To participate, students need to be strong swimmers with good underwater coordination and the ability to dive down to a depth of about 3 meters. The same cautionary notes about wetsuits above applies here as well. We will provide practice diving and measuring underwater with calipers in the class. In addition to teaching about sea urchin diversity and ecology, students on this project will learn about the use of transect and quadrant sampling, competitive exclusion and community ecology of food webs.

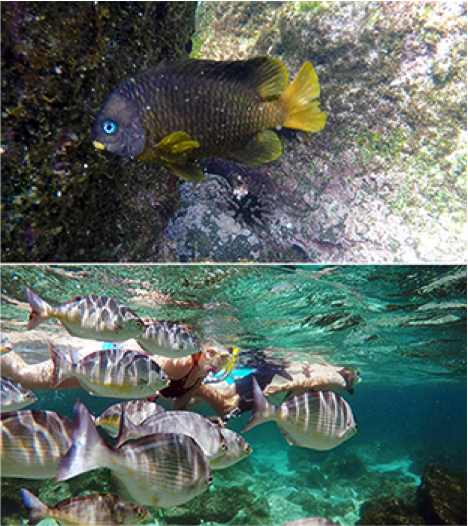

Id. Damselfish.

Two species of damselfishes found throughout the Galapagos protect territories among the rocks, using them as algae farms, hiding places, and nurseries for their eggs. This project investigates how the two species interact to divide space and food. To do this, students identify, count, and videotape damselfishes while snorkeling. In the lab, students analyze the videos to compare how the two species are distributed across rocky, sandy, or rock and sand habitats and how algae cover differs across the physical habitat. The long term goal is to determine if one species excludes the other from a preferred habitat and what the consequences are for growth and reproduction of each species.

This project includes the same study sites as the sea turtle and sea urchin projects, so it requires hiking to some locations, followed by several hours snorkeling in the cold water (and so again, a well-fitted wetsuit is helpful). To participate, students need to be strong swimmers with good underwater coordination and the ability to dive down to a depth of about 3 meters. At least one day is spent in the lab viewing and analyzing videos. Patience and willingness to concentrate on detail are required to make fish counts, characterize physical habitat, and estimate algal cover in video freeze frames. In addition to learning about the interesting life history and phenotypic diversity of damselfish, this project will teach students about the use of videography in data collection, transect sampling, inter- and intraspecific competition, and density-dependent behavior.

II. Island Health

The remaining two projects focus on the impact of humans on the health of the islands.

IIa. Water quality.

Clean water is a precious resource the world over, but particularly in places like the Galapagos where fresh water itself is scarce. This project monitors water quality from natural and non-natural sources, quantifying the kind and degree of biological contamination. The data it generates are used to refine water use and treatment policies on San Cristobal, and will influence the development of water infrastructure across the inhabited Galapagos as the human population continues to grow. In addition to field and lab techniques relating to water quality, students learn about water management and the unique challenges of water conservation on different islands in the Galapagos.

The project entails travel to numerous sites across the island (which often means some hiking), including non-costal/upland sites. Students will learn sterile lab techniques, how to make dilutions, and how to run various assays of water quality. Students with conservation, development, and health-related career plans have greatly enjoyed this project, as it not only teaches valuable lab techniques, but teaches how ecology, conservation and sustainable development are intertwined.

IIb. Sea lions and introduced diseases.

Sea lions in the Galapagos that live in close proximity to humans have a greater incidence of disease than those that live in more natural areas. Domesticated dogs, introduced to the Galapagos, can carry distemper, leptospira and parvovirus – particularly because vaccination against parvo is not permitted on the islands. This project seeks to determine if association of domestic and semi-feral dogs with sea lions poses a risk of disease for the sea lions. This project has several components; students walk transects through the town and note the location and identity of dogs twice daily. They also quantify the number, sex, age, and where possible, identity, of all sea lions on several ‘urban’ and more isolated, natural beaches. Finally, blood samples are taken from domestic dogs and sea lions to quantify disease exposure in both. Epidemiological associations are sought between the behavioral/spatial use and disease incidence of dogs and sea lions.

This project requires a few hours of walking each day, and work in the early morning and at dusk. This means that students on this project often have time to participate informally in one or two other projects while they are assigned to the sea lion project. There is also the possibility of participating in necropsies of dead sea lions, should one be found; such investigations reveal if the sea lion died from disease caught from domestic dogs. Students with interests in conservation or medicine enjoy this project greatly, primarily because the projects teach about the relationships among emerging diseases/epidemiology, development, and conservation.

IIc. Plastic contamination.

Contamination of the oceans and seas with both micro- and macroplastics is a growing concern because of their impact on animals and natural communities. On this project, students run transects in boats and on land to sample plastics from the waters and beaches around San Cristóbal. In the lab, they seek to identify the origin of these plastics. Finally, they conduct in-person surveys with tourists and residents to gauge public perception of the problems posed by plastics, to reception of new policies banning single-use plastic on the islands and to determine how effectively these policies are being implemented. It is noteworthy that working on this project had a profound impact on UH students; several narrative projects dealt with the plastics issue, and many have been moved to take action on curbing plastic use and increasing recovery of plastics since returning to UH.

IId. Petrel nest census and behavioral survey.

The Galápagos petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia) is a critically endangered seabird endemic to the Galápagos. It nests on only 5 islands, including San Cristóbal, in burrows located primarily in areas of dense vegetation cover formed by the endemic shrub Miconia robinsoniana along ravines. They are at risk of predation from introduced rodents. Moreover, their nesting grounds are becoming increasingly inaccessible due to a thorny, invasive introduced blackberry. In this project, students use flying camera drones to scout likely nesting areas. On foot, students then locate nests using GPS and assess if they are active by snaking an endoscope into the nest. They also monitor nests discovered in previous seasons. For active nests, they also determine the presence or absence of parental supervision for any brood that are present. Students use GIS to record their data. This work not only provides precise and accurate information about nest locations, parental activity, and population demographics, but also can be used to understand the response of petrels resident in the Galápagos to a non-native invader in a highly specific and vulnerable habitat. UH students have participated in this ongoing project since 2018.